Escondido Valley AVA

Sunlit Vines on West Texas Mesa

Created in 1992, the Escondido Valley American Viticultural Area (AVA) is a little‑known, high‑desert plateau straddling the Pecos River in far‑West Texas. Covering roughly 32,000 acres in Pecos County, the AVA sits on a windswept mesa 3,300 feet above sea level—higher than many Napa vineyards—where scorching days and cool, arid nights forge concentrated, low‑pH fruit. Although only a handful of commercial vineyards operate today, Escondido Valley remains a textbook case for studying how extreme heat, limestone soils, and scarce rainfall can still produce balanced wines when elevation and diurnal shift work in harmony.

Location & Landscape

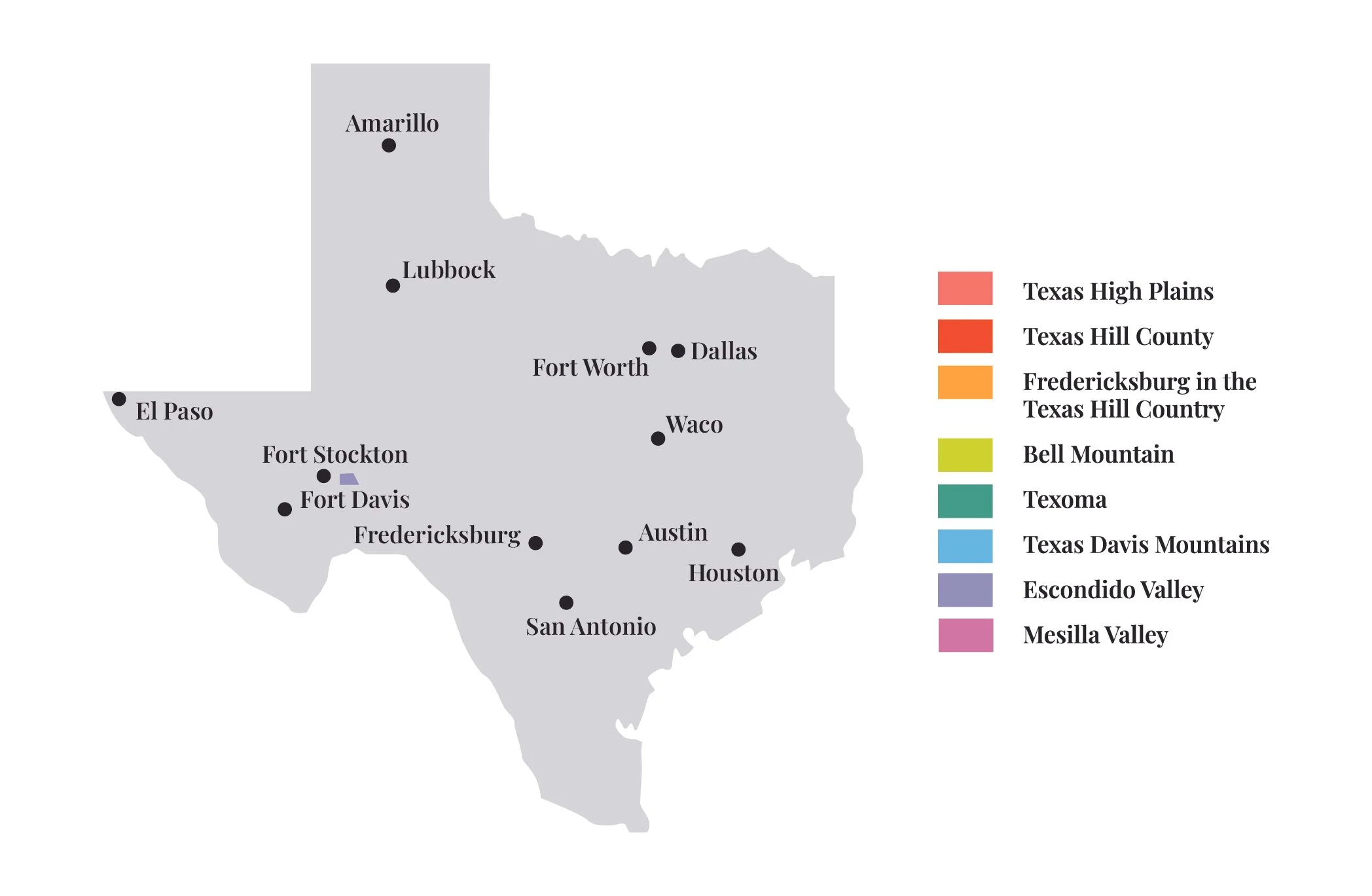

The AVA lies between Fort Stockton and the ghost town of Bakersfield along Interstate‑10—roughly 330 miles west of Austin and 240 miles east of El Paso. The terrain resembles a giant tabletop: flat to gently rolling, blanketed with mesquite, creosote bush, and tumbleweed. Elevations hover around 3,300–3,500 feet, giving vines a nightly reprieve from triple‑digit summer highs. Soils are shallow, alkaline clays over fractured limestone and caliche, forcing roots to burrow deep for moisture. The region’s vast open sky delivers 3,800 sunlight hours per year, rivaling Spain’s La Mancha.

Climate: High‑Desert Heat with Cooling Nights

· Rainfall: A meager 12–14 inches annually—making drip irrigation from deep wells essential.

· Temperature: Summer highs often exceed 100 °F, yet nights can fall into the low 60s °F thanks to elevation and radiative cooling—yielding a 35 °F diurnal swing.

· Humidity: Averaging <20 %, which slashes mildew pressure and allows near‑organic vineyard practices.

· Wind: Afternoon 20–25 mph gusts keep canopies dry but necessitate sturdy trellising to prevent shoot damage.

Key takeaway: Despite brutal daytime heat, cool, dry nights slow respiration, letting grapes accumulate sugar without sacrificing acidity—a crucial balancing act in desert viticulture.

Terroir: Limestone, Caliche & Desert Sands

Underlying bedrock comes from Cretaceous limestone and dolomite that has weathered into caliche‑rich clays and chalky sands. These alkaline soils (pH 7.8–8.3) are low in organic matter, naturally limiting vine vigor and yielding berries with thick skins and high phenolic potential. Caliche nodules reflect sunlight back into the canopy, enhancing color in red varieties like Cabernet Sauvignon and Tempranillo.

Signature Grapes & Why They Thrive

Cabernet Sauvignon - Thick skins resist sunburn; elevated nights preserve tannin balance.

Tempranillo - Spanish clone adapted to hot, arid climates; diurnal shift retains acidity.

Grenache - Thrives in drought; loose clusters minimize fungal issues.

Syrah - Handles heat; limestone soils enhance savory spice and black olive notes.

Viognier - Needs intense sun to unlock apricot aromatics; low humidity prevents rot.

Petit Verdot - Late‑ripener that achieves full phenolic ripeness in long, dry autumns.

Growers experiment with drought‑tolerant Mediterranean grapes, but Cabernet‑based blends dominate plantings—proof that Bordeaux varieties can succeed in desert conditions when elevation cooperates.

Interesting Facts

· Irrigated Oasis: Every commercial block relies on drip lines tapping the Edwards‑Trinity aquifer, enabling precision water delivery in an otherwise parched land.

· Early Vineyards: The first large planting (600 acres) in the late 1980s supplied bulk Cabernet for national blenders before Texas wineries discovered the region’s potential.

· Solar Density: With over 300 clear days per year, Escondido Valley vineyards often power pumps and frost fans via on‑site solar arrays.

· Wildlife Corridors: Vineyards share habitat with pronghorn antelope and migrating Sandhill cranes—necessitating wildlife‑friendly fencing.

Visiting & Nearby Cities

• Fort Stockton – 30 miles west; lodging hub with frontier‑era historic sites

• Marathon – 80 miles southwest; gateway to Big Bend National Park

• Midland/Odessa – 110 miles northeast; regional airport and petroleum museums

Wine tourism is still emerging—tasting appointments are essential, and most vineyards welcome students for in‑depth viticulture tours rather than walk‑in flights.

Putting It All Together

Escondido Valley teaches the ‘elevation salvation’ principle: even brutal desert heat can produce balanced wines when nights cool and soils restrict vigor. Study this AVA to understand how water management, canopy design, and varietal selection turn adversity into advantage.

· Desert viticulture demands drought‑tolerant grapes—compare Escondido Grenache to High Plains Grenache to spot desert herb and dried strawberry nuances.

· Diurnal shift is as important as absolute temperature—taste a Cabernet from Escondido next to one from low‑lying South Texas to see the acidity gap.

Next time you experience a West‑Texas Syrah bursting with blackberry, black olive, and desert sage, remember the sun‑drenched mesa and limestone caliche that sculpted its character.