Texas High Plains

Elevation-Driven Texas Wine at Its Best

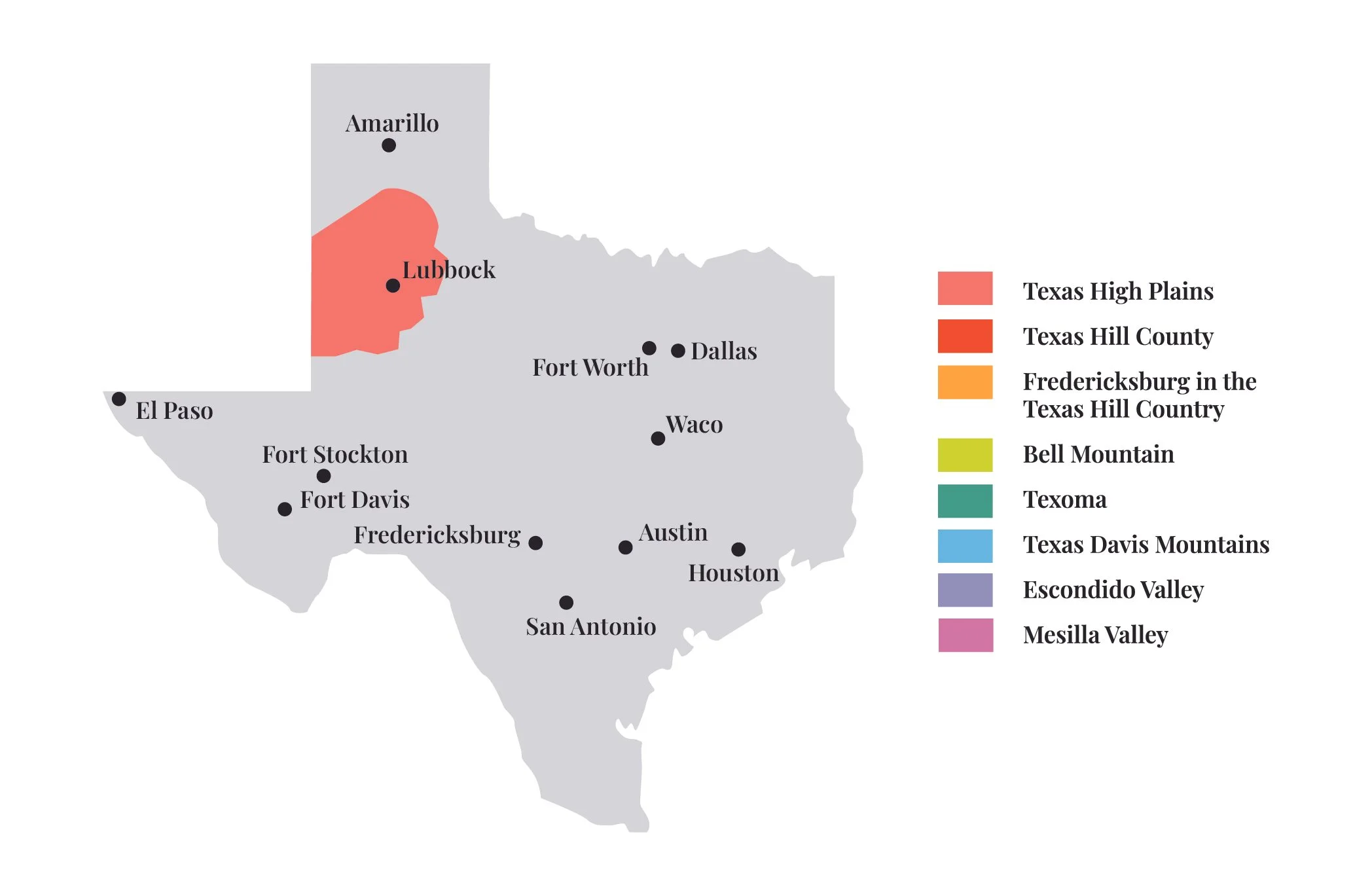

Imagine a sun-soaked plateau three-quarters of a mile above sea level, where warm days ripen Mediterranean grapes and brisk nights lock in refreshing acidity. Welcome to the Texas High Plains American Viticultural Area (AVA), formally approved in 1993 and spread across more than 8 million acres on the Llano Estacado in northwest Texas. Although most visitors first meet Texas wine in Hill Country tasting rooms, it’s the High Plains—quietly supplying about 80 percent of the state’s wine grapes—that powers many of those bottles.

Location & Landscape

The AVA covers 24 counties west of the Caprock Escarpment, surrounding cities such as Lubbock, Brownfield, and Plainview. Vineyards perch between 3,000 and 4,100 feet; those extra feet translate into cooler nights, gentler grape chemistry, and vivid colors in red varieties. Flat, powdery mesas stretch toward distant horizons, making mechanized farming efficient and hail-netting all but mandatory.

Climate: “High, Dry & Wind-Swept”

· Rainfall: Averaging ≈ 18 inches per year, half of what Napa sees, so growers rely on drip irrigation from the Ogallala Aquifer.

· Diurnal Shift: Day-night swings of 25-30 °F slow sugar accumulation and preserve acidity—vital for balance in a warm state.

· Wind: Steady 15-20 mph afternoon breezes lower canopy temperatures, reduce mildew pressure, and occasionally frighten hailstorms away.

· Growing Degree Days: Comparable to Rioja Alta or Paso Robles—warm but not blistering—favoring robust, sun-loving grapes.

Altitude is Mother Nature’s air-conditioner; it lets the region craft fresh, food-friendly wines despite Texas heat.

Terroir: Sandy Loams over Limestone

The High Plains is famous for its rusty-orange, calcareous sandy-loam soils—Pullman, Amarillo, and Acuff series are the local stars. Fast drainage forces vines to send roots deep for moisture, concentrating flavors and lowering disease risk. High pH and low organic matter tame vine vigor, while the sand itself discourages phylloxera, allowing a few daring growers to plant on own roots.

Signature Grapes & Why They Thrive

Tempranillo - Elevation mirrors Spain’s Rioja: hot days for ripeness, cool nights for acidity. Thick skins shrug off sunburn.

Viognier - Needs warmth to unlock apricot aromatics; arid wind keeps tight clusters rot-free.

Mourvèdre - Late-ripener that demands a long, dry season; handles wind like a champ.

Cabernet Sauvignon - Bordeaux classic enjoys the plateau’s UV intensity and long hang-time, while cool nights prevent jammy flavors.

Sangiovese, Grenache, Picpoul, Tannat - All hail from Mediterranean or Iberian homes—climate twins to the High Plains.

More than 75 wine-grape varieties are rooted here, giving winemakers an enormous blending palette.

Interesting Facts

· Grape Basket of Texas: Four out of every five grapes crushed statewide originate on this table-flat plateau.

· Doc McPherson’s Legacy: The AVA petition was spearheaded by Dr. Clinton “Doc” McPherson, co-founder of Llano Estacado Winery and father of modern Texas viticulture.

· Wind-Powered Cooling: Constant airflow can lower berry temperatures by 10 °F on hot afternoons—nature’s version of an evaporative cooler.

· Own-Rooted Survivors: Thanks to deep, loose sand, phylloxera struggles; a handful of vineyards remain ungrafted, a rarity in U.S. winegrowing history.

Visiting & Nearby Cities

• Lubbock (inside the AVA; home to Texas Tech’s enology program)

• Amarillo – 2 hours north

• Midland/Odessa – 2 hours south-west

• Abilene – 2.5 hours east

Tasting rooms cluster on the outskirts of Lubbock and Brownfield, but many High Plains grapes travel hundreds of miles to Hill Country wineries—so check back labels for “Texas High Plains AVA” when shopping.

Putting It All Together

Learning the High Plains teaches two core wine principles:

· Altitude beats latitude. Location on the map doesn’t doom warm-climate regions; elevation can deliver freshness.

· Match grape to place. Mediterranean and Iberian varieties flourish where cool-climate classics would fail.

Next time you sip a Texas Tempranillo bursting with red cherry and dusty spice, know that the High Plains’ thin, sandy soils and tough winds sculpted that profile.